Littering is bad. You know it. I know it. Most people, if asked, think that littering is “disgusting”.

So why does it keep building up (and what behavioural change cues can be used to stop it)?

Picking up litter costs the American economy $11.5Bn each year ($35/person). It costs the UK £1Bn (£15/person).

For the USA, that’s a sum bigger than the GDP of a third of the world’s countries solely spent on picking up discarded trash ranging in size from sweet wrappers to TVs, tyres and fridges. The UK even sees the odd coffin added to the mix.

But it’s just money, right?

Woah there. Yes, it’s a big economic problem (how many schools/hospitals can be built for that cash? How many teachers/doctors trained and employed?) but it’s wider than that:

- Litter has a detrimental effect on the natural environment, especially marine environments (you need to be particularly concerned about this if you eat fish)

- The presence of litter affects perception of property prices and business growth

- A Dutch study suggests that high levels of littering act as ‘permission’ for other crimes, including graffiti, trespass and even stealing money

- Rubbish has the potential to start fires – as this frankly terrifying PSA from 1980’s Britain tells us (we still have the issue today)

- A study published in the American Journal of Epidemiology found that “the amount of litter was inversely associated with the odds of both occasional and infrequent exercise” [which presumably correlates to…]

- The presence of trash/litter is a predictor of levels of obesity in a neighbourhood, according to a study published by the NCBI

- The indirect costs of littering are enormous, dwarfing the costs of picking up the rubbish in the first place.

Dirty, dirty people

Yes, and no.

Not all litter-droppers are created equal. Looking at research from the State Government of Victoria, Australia (as well as a wide-funnel online literature review), a few typologies emerge:

- Those who are just careless, allowing things to blow from picnic tables, vehicles or pockets

- Those who drop gum, paper, wrappers or small items because it’s too inconvenient to dispose of the item properly (but who wouldn’t dump, let’s say, a fridge)

- Those who go out of their way to fly tip enormous amounts of waste with little or no regard for the damage that it’s doing to the surrounding area.

For behavioural change practitioners, these typologies (alongside others) are a useful shortcut to thinking about the different motivations contributing to this $billion problem.

Moving EAST to Cialdini’s Car Park

Even the briefest literature review suggests that there are a multitude of reasons why people drop litter, even though they believe that it is wrong to do so (let’s exclude the environment trashing fridge/TV/dead porpoise dumpers for the moment).

In my opinion, a number of these revolve around the EAST framework:

- Easy – it is easy to properly dispose of litter in the place that you’re in (after all, we could all carry our trash home with us)? Or easy enough to hold onto the litter until an opportunity presents itself?

- Attractive – why would disposing of litter correctly be attractive? Could it be made fun, or made to chime with a deeper behavioural lever that you already have?

- Social – what are the social norms around dropping – or importantly – picking up litter? What happens with in-group behaviours? Additionally, what does the environment tell us to do?

- Timely – Are there places to correctly deposit litter when you need them? Is the facility available at the right time?

For E & T, one could argue that well positioned bins or disposal points are a good answer (so long as they are regularly emptied). The State of Victoria research previously referenced suggested that 26% of people littered because there was no bin in the vicinity, a finding which is borne out in many other studies, so ‘Ease’ and ‘Timeliness’ are going to be key and could cut down on a lot of the issue.

Hang on. Italics. Could?

Our experience of the environment also has a lot to do with our littering behaviour. Cialdini, Kallgren & Reno spent a lot of time hanging out in car parks testing normative conduct theories into littering behaviour.

What they discovered was that if an area is already littered, individuals are more likely to contribute to the general trash levels than if it was a clean environment.

This is significant, especially if you consider the apparently dissonant position some will find themselves in where they would not describe themselves as a litter, yet also self-evidence littering behaviour (62% of the UK population for example drop litter, yet 86% of people think it’s wrong to do so. Therefore there is presumably a cross-over where behaviour contradicts attitude, causing some dissonance).

The sub-text in littered areas is, of course, that if everyone else is doing it, then it must be OK.

Which probably explains how littering can become a vicious cycle – just look at what’s been reported in Cardiff recently (even when there are bins within easy reach at the time of needing to dispose of the litter).

What’s also interesting about Cialdini’s study is that it supports the idea that seeing someone else pick up litter influences the viewer’s behaviour, establishing an injunctive norm that suggests ‘this is not a place to litter’.

This therefore suggests to me that both people and place have a significant effect on an individual’s propensity to litter, even disregarding other factors (such as descriptive norms provided by advertising/other cues or punishment).

However, the punishment fairy isn’t always real

Most developed countries have laws against littering, ranging from escalating fines and/or community service (see this USA example or this first person account from the UK) and, in more extreme countries, having your car confiscated.

However, these aren’t exactly effective (if they were, we wouldn’t be having this discussion). Fast.Co reports that the threat of fines in Illinois has done little to curb cigarette litter.

In my opinion, fines in the UK hold little weight for ‘pocket lint litter’ (bits of paper, wrappers, cigarette butts etc) since one can observe vast quantities of these littering the streets on a regular basis. Waghorn-Lees, Fantetti, Ditzian and Dunlop (2013) also suggest that the uncertain nature of punishment means that fines on their own are “unlikely to be effective” drivers of behavioural change and given that only 15% of people are likely to confront a litter-er leaves a lot of time/space that authorised individuals (police, council workers etc) simply can’t observe, and hence can’t enact punitive measures.

The dual issues of proportionality and scale

To those who don’t see dropping a bit of gum or paper an enviro-crime (as they would for dumping old tyres perhaps), the methods of detection and punishment are likely to seem disproportionate to the crime in question (for example the uproar from these litter wardens who, if research into the unacceptability of littering is to be believed, probably should be lauded).

And those same people are, I would expect, quite unlikely to see their ‘insignificant’ gum or single fag butt as deserving of a £75+ penalty.

Equally, looking at scale, if the environment already has litter within it, there may be the perception that “one more bit won’t hurt”.

Additionally, because the behaviour is carried out and the person then moves on , the litter almost instantly becomes someone else’s problem. If the litter were to follow the person around, my expectation would be that it would be dealt with very differently!

What’s a behaviouralist to do?

There are a number of levers available to behaviour change practitioners interesting in addressing the litter scourge without resorting to punishment.

Look at the problem differently

Changing frames of reference can be effective in changing behaviours. If traditional messages have focused on the broad environment, why not focus in on a specific element and action within that environment to nudge behaviour?

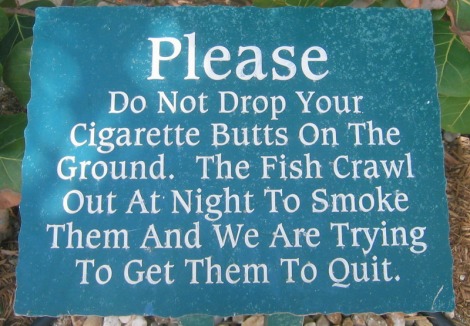

I love these two examples:

(Thanks to Barbara Hopkins for the second image)

Both of these examples are incredibly specific – detailing what you should not drop, where you should not drop them and why – and change the frame of reference from broad environmentalism to salient micro level activity.

Coins being thrown into a creek might not be ‘litter’ in the trash sense we’re all used to, but if they disrupt the natural order and adversely affects the ecosystem, they may as well be.

They also achieve a fantastic degree of cut-through by using humour. Would they be as memorable if they were standard anti-littering signs with some dullard message about the level of fine you’ll receive if you’re caught? Highly unlikely.

Tap into culture and place

My absolute favourite here is ‘Don’t Mess With Texas‘ which taps into an incredible depth of feeling & pride Texans have about their state (and about each other) – an act against the state can therefore also be seen as an act against the individual or community unit.

‘Don’t Mess With Texas’ is a great way to create in-group and out-group differentiation (in-group being those who don’t mess, out-group being those who do), as well as using strength of language to drive home the point.

It’s also relevant to all sectors of society (resident, visitor, business) as it is specific about the ask. In contrast, campaigns such as ‘Keep America Beautiful’ or ‘Keep Britain Tidy’ offer more ambiguity (beauty is, after all, in the eye of the beholder and just what is tidy anyway – a well manicured hedge can be ‘tidy’ and it has a number of different slang associations).

If there’s a cultural code that can be sensitively appropriated, it’s probably worth exploring. In Texas, for example, the code is going to be that it’s ‘unTexan’ to trash Texas…

Use social norms

As Cialdini demonstrated, environmental litter attracts more litter, and just seeing another person act in a certain way modifies behaviour.

Social norms around clean places and clean people can start to establish injunctive norms and modify behaviour before the act of (or even decision about) littering occurs.

Even Coca-Cola are considering how to use social influence & pressure to change behaviour and reduce litter (it could be argued that this is in their implicit interest as they are unlikely to want images of their bottles in gutters being used to typify the waste problem – however that’s not a bad lever to use if you’re working at a corporate level).

Use rewards and incentives

It’s not easy to reward anti-littering behaviour – after all, if you can’t see someone to fine them, then you can’t see them to reward them.

However, Neat Streets in the UK overcame this beautifully. Not only did they flash-mob-thank people who picked up litter to put in the bin, but they actually installed bins which made strange noises when you used them, rewarding the behaviour of throwing something away. (Talking bins appear at 1:10, Flash Mob at 1:20)

Another way to consider incentivising behaviour is to look at offering cash-back on plastic bottle deposits encouraging people to take them home and store them for a later financial reward. This has the added bonus of making recycling transactional rather than theoretical (put it in a bin and it becomes someone else’s problem). #

A great example here was the way that John & Ann Till paid for their honeymoon flight through recycling waste (much of which had been rolling the streets as litter) at Tesco. Every little did indeed help…

Make it easy

Another superb example from the Neat Street video is the Gum Drop ball (there are similar products on the market for cigarette ends, a further contributor to litter). This makes it super easy for people to store their gum prior to disposal and to see it get turned into something useful.

Make it personal

de Kort et al looked at how the design of trash bins – and the messaging placed on them – could activate personal norms. Given that other research overwhelmingly shows that most people thing littering is a bad thing, it’s reassuring to see that their experiment – which required viewers in the natural field to reflect on their intended reaction to being given a flyer – resulted in an uptick of people choosing to dispose of the unwanted paper appropriately.

Although a personal appeal may not be effective if framed against reducing ‘trash mountains’ or battling ‘floating islands of waste’, causing people to judge their intention against their implicit normative standards seems to be helpful.

Find diversionary activities

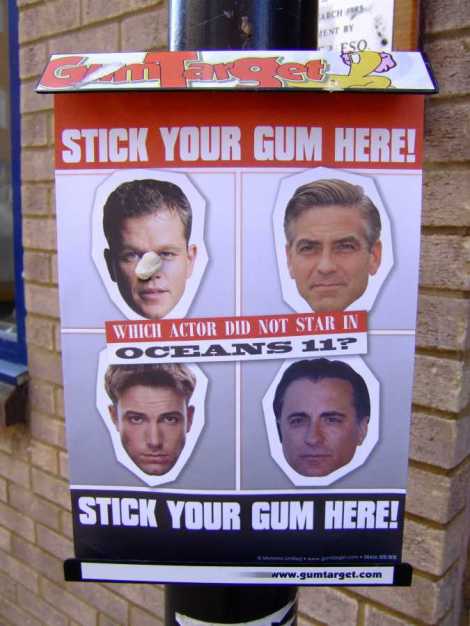

People chew gum, and people are unlikely to stop chewing gum. That’s fine – the issue is the disposal.

And, of course, this is even more pressing at high dwell time locations – theme park lines, sports stadiums, bus stops where you equally don’t want the gum stuck to seats or walls.

One idea I’ve seen is this GumTarget – a clever way to direct the disposal activity in a really high profile way which also plays on social norming levers because it’s obvious that everyone else is playing along and this is the ‘done thing’ to be doing.

(Hat Tip to the Nudges blog for this exact image)

If you want to see a similar idea but for cigarette butts – you’re in luck!

https://twitter.com/SoccerMemes/status/767149220054917120

Don’t use images of litter

This last one seems counter-intuitive. However, if you’re telling people not to litter and using images that suggest the social norm is to drop litter, I think that it’s likely that your message is going to get confused at a subconscious level.

Don’t forget – images do the job of a thousand words…

It’s a big job…

Littering has been an issue for decades. And, with the volume of waste blowing around at the moment, will be an issue for decades to come (even if not so much as a chocolate wrapper is dropped from here on out).

It is, however, fertile ground for behaviour change and social marketing professionals to make a demonstrable, lasting, impact.

Who’s up for an £11.5bn challenge?